DHAKA: Across the campus of University of Dhaka, corridors are layered with fresh graffiti anger, satire, poetry, all echoing the student-led uprising of July 2024 that ended the 15-year rule of the Awami League. Students sit in small circles debating politics, while red lanterns for Lunar New Year hang above a patch of grass where arguments about democracy blend with talk of dignity and the future.

Bangladesh goes to the polls on 12 February. But in Dhaka, this feels less like a routine vote and more like a national reset after a turbulent chapter.

A Generation That Refuses “Old Politics”

On campuses and in cafés, students say they are exhausted by what they call “old politics.” Their vocabulary is different from party slogans: jobs, fairness, corruption, freedoms, respect.

Some of the youth leaders who emerged during last year’s protests have stepped into formal politics through a newly formed platform and even entered electoral understandings with the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. That move has energized some and unsettled others, but it has one clear effect: youth are no longer only protesting — they are participating.

“We don’t want party change, we want system change,” a student told Pakistan Narrative.

Life After the Awami League Era

The fall of the Awami League government in 2024 remains the emotional backdrop of this election. Many people speak in hushed tones about the violence of that period and the grief that followed. Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus stepped in to lead an interim administration, creating space for political reorganization and public debate.

With the Awami League barred from contesting, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) is attempting to occupy the political center. Party workers are visible, but the louder presence on the streets is that of ordinary citizens discussing what they hope will not return.

The fact that Sheikh Hasina lives in exile in India is mentioned frequently in conversations not as gossip, but as a symbol of unresolved grievances.

India in Everyday Conversations

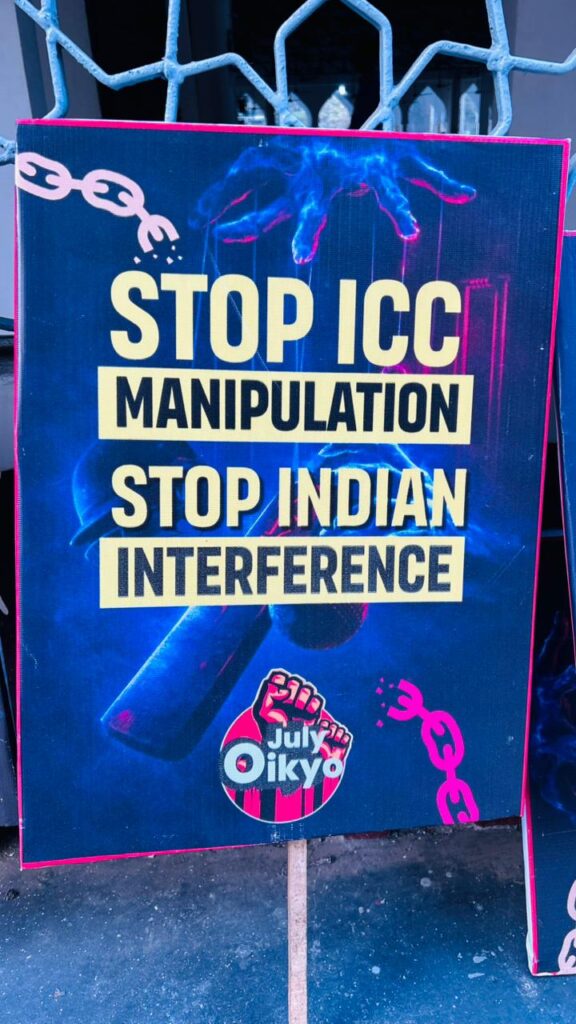

Mentions of India surface naturally in Dhaka’s political chatter. Words like respect, sovereignty, and dignity recur. Many Bangladeshis feel that India’s past approach to Dhaka favored stability over democratic scrutiny, and this perception has hardened since 2024.

Yet this sentiment is nuanced. Criticism of Indian policy does not translate into hostility toward Indian people. A cultural activist explained: “Our issue is with governments and policies, not with people. Our families, culture, and history are connected.”

Despite political tension, traders point out that energy supplies, textile inputs, and transit arrangements with India continue. The strain, locals say, is emotional and political more than economic.

China, Pakistan, and Strategic Space

At the same time, Bangladesh’s outreach to China is widely noticed. Infrastructure cooperation and new agreements are seen as Dhaka seeking broader strategic room rather than choosing sides.

There is also quiet discussion about Dhaka reopening channels with Pakistan after years of distance. Locals frame this as expanding options in a new political phase, not as alignment.

A shopkeeper summarized the public mood: “Good relations with everyone, dependence on no one.”

Competing Narratives and Media Battles

Another layer to this election is the battle of narratives. Indian media reports alleging widespread attacks on minorities are strongly disputed by officials here, who argue that isolated incidents are being portrayed as systematic persecution. These competing claims are debated in newsrooms and across social media, adding intensity to public discourse.

Students say social platforms shape opinions faster than television. Rumors, counter-claims, and political messaging travel rapidly, making perception as important as policy.

A Campaign of Pragmatism

Interestingly, even parties known for strong rhetoric are speaking in pragmatic tones about foreign relations during the campaign. Leaders from the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami emphasize stability, trade, and dignity in regional ties.

Candidates appear aware that repairing relationships with neighbors will be essential after the vote regardless of who wins.

What Voters Want

Across markets, campuses, and sidewalks, one phrase repeats: stability with dignity.

Voters want confidence restored at home and respect secured abroad. They want an election that feels credible and a government that feels accountable.

As one student put it: “We want Bangladesh respected everywhere — not fighting with anyone.”

An Election Felt in Conversations

In Dhaka, this election is visible less in grand rallies and more in everyday conversations on benches, in classrooms, at tea stalls. It is shaped by memory, emotion, and expectation.

For observers in Pakistan and across South Asia, the message from Dhaka is clear: Bangladeshis are not only choosing representatives. They are redefining how their democracy should feel and how their country should be treated.